From Artillery to Automotive: Over a Century of Proven Performance

Let’s start by breaking down the word oleo-pneumatic.

Oleo means "oil", and pneumatic means "containing air or gas under pressure."

Oleo-pneumatic technology was invented in the early 20th century. The first practical application is credited to the French engineer Paul Doumer, who developed the oleo-pneumatic shock absorber for military artillery in 1908. His invention allowed artillery to recoil smoothly without destabilizing its position, improving accuracy and operational efficiency.

The Vickers machine gun and other rapid-fire weapons incorporated oleo-pneumatic mechanisms later to manage the forces generated by their automatic fire. This adaptation allowed smoother operation and reduced wear and tear on the gun mechanisms, improving reliability in battlefield conditions.

In 1925, George Messier, a French engineer, had the idea to use this concept to install the first suspensions of this kind on a car. The "springless car" was an immediate success, with over 150 vehicles sold with this technology.

Later, as oleo-pneumatics became the standard for airplane landing gear, Citroën, followed by Mercedes and Rolls Royce, adopted this technology under the guidance of another French engineer called Paul Magès and used it for over 60 years with the legendary success we know.

The tech has come a long way since the early 1900s, but it's still the go-to solution when you're dealing with a heavy load and lots of oscillations in the terrain. And by the way, almost every commercial and governmental aircraft still uses oleo struts in their landing gears. It's a rock-solid technology that has stood the test of time.

More exclusive nowadays due to its production cost, it remains the only approach that can uncompromisingly ensure the trio of "comfort, safety, and performance.

HOW DO OLEO-PNEUMATIC SUSPENSIONS WORK?

Nimbus oleo-pneumatic suspension systems combine advanced gas-fluid dynamics with high-precision damping architecture to deliver exceptional performance, adaptability, and endurance.

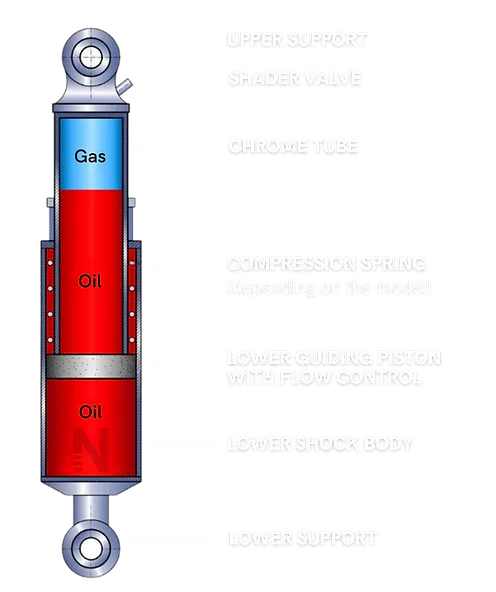

Within each unit, nitrogen and hydraulic oil operate together under pressure, forming a stable emulsion during motion.

Unlike simpler designs that rely on fixed mechanical springs or isolated gas chambers, this integrated approach allows for far greater responsiveness, but also demands much more precise engineering and tuning.

Under compression, the nitrogen gas acts as a progressive spring, with its pressure rising exponentially as volume decreases. This non-linear response enables the system to absorb small vibrations with sensitivity while still managing large shocks with authority.

Meanwhile, the hydraulic oil is forced through a complex arrangement of calibrated valves, spring-loaded flaps, and precision orifices, delivering highly controlled resistance during both compression and rebound phases. This viscous damping process converts motion into heat, which is dissipated within the fluid, ensuring stable behavior even under repeated or prolonged stress.

The interaction between gas and oil in the emulsion adds yet another layer of complexity: changes in internal pressure must simultaneously preserve damping consistency and maintain the desired spring behavior.

Tuning this balance is not trivial. It requires expertise in fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and mechanical response curves. This is not a “one-size-fits-all” system; it’s a finely calibrated instrument.

To put it in perspective: think of conventional suspension systems like analog wristwatches; effective, reliable, but limited in nuance. Nimbus’s oleo-pneumatic setup is more like a mechanical chronometer used in aerospace: far more complex, requiring precision adjustments, but capable of delivering unmatched accuracy and performance when every variable matters.

When you receive your Nimbus, they are perfectly tuned for you, your vehicle as it is, and what you intend to do with it.

But we know that life happens.

Thanks to the ability to adjust nitrogen pressure, each Nimbus suspension can be tuned to support significant load variations - up to 800 lbs (around 400 kg) - without compromising comfort, ride height, or control. The result is a system that adapts in real time to changing conditions, terrain, and usage.

Nimbus suspensions are not simplified alternatives. They are the result of advanced engineering, built to thrive where others technologies could fail. From rugged overlanding to mission-critical utility, their refined performance is driven by a symphony of gas compression, fluid regulation, and mechanical control, delivering smoothness, strength, and trust... on any surface, under any load.

WHAT ABOUT SPRINGS?

There’s a lot of understandable confusion when it comes to springs and Nimbus suspensions.

Questions like:

“Should I keep my springs or replace them?”

“Why not switch to 100% oleo-pneumatic?”

Let’s clear things up, especially if you're installing a Vibranium generation.

A traditional suspension system relies on two core components:

• springs to support the vehicle’s static load, and

• shock absorbers to control motion and dissipate energy.

Nimbus changes that by replacing the conventional shocks with oleo-pneumatic units, each one acting as a dynamic spring-damper hybrid, using compressed nitrogen gas as a highly progressive, tunable spring, and hydraulic oil to control rebound and compression.

So technically, you now have two types of springs working in tandem:

The physical springs (coil, leaf, or torsion bar, depending on your vehicle), and the nitrogen spring inside each Nimbus unit.

Why Keep the Physical Springs?

While our oleo-pneumatic units are capable of absorbing both minor vibrations and major impacts, they were designed to complement - not replace - your vehicle’s primary spring system on most models. The physical springs play a critical role in supporting the static weight of the vehicle and preserving the structural integrity of your chassis.

Automotive engineers design suspension architectures with load-sharing in mind. In most vehicles, the shock mounts are not engineered to carry full vehicle weight, especially during large impacts. Removing the original springs would transfer forces directly through the Nimbus units to these mounts, exceeding their design limits and potentially compromising the chassis over time.

In other words, removing your springs is just unnecessary and risky, unless the entire system has been re-engineered to support that configuration.

But What About Goliath V2?

With Goliath V2, it's different.

This system is designed as a true 100% oleo-pneumatic solution that fully replaces the traditional spring and shock assembly. By deploying dual high-capacity units per wheel, usually in the front, we can get rid of metal springs because we simply install them where coil overs were, allowing the vehicle to ride entirely on nitrogen pressure and oil damping.

But unless you’re running a Goliath system, springs are still part of the equation.

Choosing the Right Springs with Erebus

That brings us back to your original question:

“Should I keep my current springs?”

In most cases, yes.

We design Nimbus Erebus units to work in harmony with OEM spring rates when possible. When your vehicle is stock or close to it, there’s rarely a need to change anything.

However, if you’ve already upgraded to heavier springs to carry gear, armor, or accessories, we’ll take that into account. During your post-order discovery process, we’ll review your setup together and determine whether the springs you’re running are compatible with the ideal Nimbus performance envelope.

If they’re not, we’ll recommend replacements, typically progressive springs, that we will select for your exact vehicle and configuration. You’ll have the option to purchase them directly or through us, depending on what’s easiest for you.

PRINCIPAUX AVANTAGES DES SUSPENSIONS OLEOPNEUMATIQUES NIMBUS

confort amélioré

La combinaison air et huile popularisée par Citroën et plus tard, Mercedes et Rolls Royce, offre un confort de conduite incomparable. La technologie oléopneumatique de Nimbus absorbe les petites imperfections de la route tout comme les pièges en tout-terrain, à haute comme à basse vitesse.

haute-performance

Les suspensions Nimbus offrent une adhérence et une capacité traction exceptionnelles grâce à un rebond ultra-rapide qui vient coller la roue au sol bien plus vite que les suspensions traditionnelles. Ainsi, le véhicule transforme mieux l'énergie en mouvement, améliorant ainsi la motricité, les performances et la sécurité de l'ensemble.

100% adaptables

Vos suspensions sont fabriquées sur mesure pour votre véhicule, et pour l'usage que vous souhaitez en faire. Mais à tout moment, la pression de l’air peut être ajustée, garantissant ainsi le même confort et les mêmes performances, quelle que soit la charge du véhicule et votre style de conduite.

haute sensibilité

Les suspensions Nimbus offrent une courbe de compression progressive avec une sensibilité accrue en début de course, qui vient absorber les petites imperfections du revêtement. C'est ce qui provoque cette sensation de flottement totalement contrôlé avec l'effet dit "Tapis Volant" ou "Nuage".

absence de talonnage

L’air est l'ingrédient secret qui empêche les suspensions de talonner même dans des conditions extrêmes. Là où les amortisseurs conventionnels apportent une réponse quasiment linéraire, les amortisseurs oléopneumatiques vont s'adapter à chaque sollicitation, les plus douces comme les plus violentes, empêchant ainsi tout talonnage.

légèreté

Les suspensions Nimbus sont plus légères que la plupart des systèmes de suspension conventionnels. L’utilisation d’aluminium de très haute qualité et d'autres matériaux venant, entre autres, de l'aérospatiale, nous permet de réduire le poids de nos produits tout en offrant une solidité et une résistance à la corrosion exceptionnelles.

Why Nitrogen?

At Nimbus, we use pure nitrogen to pressurize our suspension units and that’s a deliberate engineering choice.

While air might seem like a simpler or more accessible option, nitrogen offers several key advantages that make it far superior for long-term suspension performance.

Unlike ambient air, nitrogen is dry, chemically inert, and thermally stable.

This means that the gas inside your Nimbus unit won’t react with the internal components, won’t introduce moisture, and won’t vary unpredictably with changes in temperature.

Oxygen and water vapor - both present in regular air - can lead to pressure fluctuations, and inconsistent damping behavior over time. Nitrogen avoids all of that.

It could also lead to internal corrosion, but that’s not really a concern here. We use high-grade materials, especially aerospace-grade aluminum, that are naturally resistant and unaffected in this context.

With nitrogen, whether today or ten years from now, the physical and chemical properties of the gas inside your Nimbus will remain unchanged. There’s no need to replace it, no risk of internal degradation, and no shift in performance. The gas is there to stay, and it will perform just as precisely and consistently in the long run as it did on day one.

That said, we also recognize the real world isn’t always perfect.

If you ever need to adjust the pressure while out in the field or in a remote location, using regular air is entirely acceptable. It’s not ideal for permanent use, but it won’t damage the system, and it will keep you going until you can refill with nitrogen, even if it takes months. That’s part of the robustness of our design: high-performance when conditions are optimal, but also forgiving when they’re not.

So yes, we use nitrogen because it’s the best choice for durability, stability, and performance. But if you ever need to top up with air, don’t worry, your Nimbus won’t mind.

and if you have more QUESTIONS,

WE'VE GOT more ANSWERS.

What materials are used in Nimbus suspensions for 4x4?

We source only the best of the best materials and components on the market. Think military-grade muscle and aerospace-level finesse, all in the name of longevity and customer satisfaction.

The components of Nimbus shock absorbers are made in our factory using two types of aluminum (aluminum 7175 and aluminum 6082), chromoly, and steel 45Si7. The steel tubes undergo a "Hard Chrome" treatment to further enhance corrosion resistance.

Is the high-pressure pump provided with the suspensions?

We don’t automatically include a pump with the purchase of Nimbus suspensions for one simple reason: they come fully pre-set and ready to perform.

Each unit is factory-charged with nitrogen, precisely calibrated to match your specific vehicle and its expected use. That means no adjustments are needed right out of the box.

That said, if you ever wish to fine-tune the pressure, you absolutely can.

Every Nimbus unit is equipped with a schrader valve, a universal standard found worldwide. This gives you the freedom to use most high-pressure pumps that can reach the required PSI.

And here’s some good news: most of our Vibranium suspensions are designed to operate at relatively moderate pressures, which means you can often make adjustments using a regular workshop compressor. We engineered this on purpose, for your convenience, so you don’t need specialized equipment just to dial in your ride.

What is the impact of your suspensions on the tire wear?

Nimbus suspensions have no negative impact on tire wear when installed correctly.

However, as with any suspension upgrade, we strongly recommend performing a wheel alignment check and tire balancing after installation, even if the ride height hasn’t been modified.

Why?

Because even small changes in suspension geometry or damping behavior can slightly alter how weight is distributed across your tires. Ensuring proper alignment helps maintain even tire contact with the road and prevents irregular wear over time.

This isn’t specific to Nimbus. It’s simply good practice whenever any suspension component is replaced. A quick alignment check means your new ride will feel better, handle better, and your tires will last longer.

Are the suspensions reliable in extremely low temperatures like around the Arctic Circle, or extremely high temperatures?

Absolutely. Nimbus suspensions are engineered to perform reliably across a wide range of extreme temperatures, from arctic cold to desert heat. Whether you're operating in sub-zero conditions or under intense sun, your suspension won’t let you down.

In fact, our units are designed to function between –100°C and +280°C, well beyond any temperatures you’re likely to encounter on Earth.

That said, real-world performance isn’t just about material limits, it’s about responsiveness and consistency. And that’s where Nimbus shines.

In very cold environments, such as northern Canada or the Arctic Circle, you may notice a slight change in behavior during the first few minutes of driving. This is completely normal. Our systems warm up quickly once in motion, and damping performance stabilizes after just a few hundred meters.

If you regularly drive in extreme climates - whether freezing winters or scorching summers - let us know when you order. We’ll fine-tune the setup specifically for your conditions so you get the most out of your Nimbus system year-round. You might also consider small seasonal adjustments to internal pressure for optimal comfort and performance. This is especially relevant in regions with large temperature swings between seasons.

What justifies the cost of the Nimbus suspensions?

Nimbus suspensions come at a higher upfront cost than traditional systems, but there's a reason for that, and it's all about what you're actually getting.

First, oleo-pneumatic technology is inherently more advanced and expensive to produce than standard coil-over or monotube shocks. Each component - valving, materials, seals, gas handling systems - is built to a much higher specification, with precision manufacturing and tight tolerances.

We're not working with off-the-shelf parts; every Nimbus is engineered and assembled to perform at a level far beyond conventional suspension systems. When you compare Nimbus to other high-end, performance-grade suspensions, you'll find our pricing is well within the same range, but with the added benefit of a unique technology that delivers both comfort and control in a way few systems can.

What also sets Nimbus apart is longevity.

Most suspensions are considered wear parts and must be replaced regularly. Nimbus units, on the other hand, are fully rebuildable and designed to last the lifetime of your vehicle. Instead of replacing them every 50,000 or 100,000 kilometers, you simply service them when needed, if needed.

It’s a one-time investment that pays off over the years, both financially and mechanically.

And there’s a sustainability angle too: by avoiding repeated replacements, you reduce waste and lower the overall carbon footprint of your suspension system. It's a smarter choice for the planet, and for your wallet.

In short, Nimbus suspensions aren’t just parts. They're a long-term upgrade to the way your 4x4 rides, performs, and endures.

How often do I need to fill the suspensions with air?

In short: you don’t.

Every Nimbus suspension is pre-filled at the factory with nitrogen, precisely calibrated based on the details you provided about your vehicle.

Once installed, there’s no need to adjust or refill the pressure under normal conditions. It’s important to understand that Nimbus suspensions are sealed systems. The nitrogen inside is chemically stable and does not degrade or leak over time. That means no regular top-ups, no pressure loss, and no maintenance required unless your setup changes significantly.

If you do decide to adjust the pressure manually - for example, after adding or removing a major load - you can use a high-pressure pump or even a regular compressor most of the time, via the built-in Schrader valve.

Just keep in mind that once you connect a pump and make adjustments, air will begin to mix with the nitrogen inside the unit. While this introduces a bit of moisture and slightly increases sensitivity to extreme temperatures or altitude changes, it’s nothing to worry about. Your Nimbus will continue to perform as intended.

As a general guideline, you only need to adjust the pressure if you make a substantial change to your vehicle’s weight - typically more than 400 kg (about 800 lbs) on one axle. This might include adding a camper shell, extra fuel tanks, or other heavy gear.

Otherwise, just install, enjoy the ride, and let Nimbus take care of the rest.

Do I need to send the suspensions back to your factory for maintenance?

Not necessarily.

While we recommend a service every three years for peace of mind and optimal performance, it’s not mandatory. This is a guideline based on our internal quality standards, not a requirement of the warranty.

If you choose to follow this recommendation, you can send your Nimbus suspensions to our factory in Saint-Gaudens, France, where they’ll be fully inspected, cleaned, and serviced to factory specifications. The full service typically takes up to 10 working days, excluding transport time.

We also know that shipping components across borders isn’t always convenient. That’s why we’re building a global network of certified workshops, trained and equipped to carry out Nimbus maintenance using the same procedures and original parts as our factory. This ensures you’ll have access to reliable service wherever you are.

And if downtime is an issue, consider our Trade-In Program. If you're eligible, you can upgrade to the latest version of Nimbus, fully customized to your vehicle, before even sending your current units back. That means no waiting, no shipping delays, just a seamless swap and you're back on the road in a matter of hours, with the best suspension we’ve ever built.

If you're due for service or simply want to explore your options, reach out. We’ll guide you to the best solution based on your location and setup.

Can I use all types and sizes of tires for my 4x4?

Yes, as long as the tires are appropriate for your vehicle’s brand and model, and as long as we know it before building your Nimbus.

Nimbus suspensions are designed to work seamlessly with any tire size that is mechanically and legally compatible with your 4x4. Whether you're running stock tires or oversized off-road ones, the suspensions will adapt without issue.

Just make sure your chosen tire size fits within your vehicle’s factory tolerances or approved modifications. Our system won’t be the limiting factor.

Can I adjust the ride height with these suspensions?

This is a common question and the confusion is understandable.

So let’s clear it up. Nimbus suspensions are oleo-pneumatic, not air suspensions.

That means you cannot raise or lower your vehicle at the push of a button, as you would with air systems. Oleo-pneumatics use a completely different principle, one that dates back over a century and is still unmatched in terms of comfort, control, and reliability.

While air suspensions are designed to alter ride height dynamically, our oleo-pneumatic system focuses on something else: delivering exceptional ride quality, superior grip, precise energy transfer, and reduced body roll, all while remaining incredibly robust.

If you’re after a smoother, more controlled ride without compromising performance or reliability, you’re in exactly the right place.

That said, Nimbus units can be built in different lengths to accommodate specific setups. And once installed, you may see a small variation in resting height - just a few millimeters - depending on the internal pressure.

But this isn't a system designed for on-the-fly height adjustments. It's a system designed to perform flawlessly across every mile.

Do I need to modify my vehicle to install your suspensions?

No modifications are needed.

Nimbus suspensions are designed to be plug-and-play replacements for your original shock absorbers. They fit directly onto your vehicle using the factory mounting points, with no cutting, welding, or structural changes required.

That’s one of the key advantages of our approach: you get a high-performance oleo-pneumatic system, built to handle extreme conditions, without compromising the integrity of your 4x4.

In short, installation is straightforward, and your vehicle stays just the way the engineers intended, only better.

Can I change my springs after installing your suspensions?

Yes, but with caution.

Your Nimbus suspensions are specifically designed and tuned based on the exact configuration of your vehicle as it was described to us at the time of production. That includes working in harmony with the springs (or torsion bars) you already had, or with the springs we recommended if a replacement was necessary.

If you decide to change your springs afterward, whether by installing stiffer, softer, or different-length springs, you may alter the balance and behavior of your Nimbus system. It won’t necessarily damage anything, but it could affect ride quality, comfort, or performance.

That’s why we always recommend contacting our technical team first.

Just send us an email with the details of your setup or project, and we’ll review it together. We’ll help ensure your new spring choice won’t negatively impact how your Nimbus performs.

And of course, this advice and support is completely free.

What happens if I add weight to my vehicle?

Adding significant weight - whether at the front or rear of your 4x4 - will naturally change how the vehicle behaves in terms of comfort, handling, and efficiency.

The good news is that Nimbus suspensions are built to adapt.

Thanks to the oleo-pneumatic system, you can fine-tune the internal pressure to adjust the spring stiffness with incredible precision. If you add weight, simply increase the pressure. If you remove weight, reduce it.

The adjustment process is quick and effective, with near-infinite control over how your suspension responds. This is especially useful for setups that change often, such as vehicles that carry a removable camper, water tank, or rooftop gear for part of the year but are used daily the rest of the time.

Once the pressure is adjusted, comfort and performance are preserved, regardless of the load. As a general rule, we recommend adjusting the suspension pressure if you add or remove more than 400 kg (around 800 pounds) continuously on one axle.

And if you’re unsure about your setup or need help dialing in the right pressure, just reach out. Our technical team is here to guide you toward the best configuration, quickly and free of charge.

And in more extreme cases, where the weight added or removed is substantial and permanent, you can even send your Nimbus units back to us. We’ll reconfigure them - and will take this opportunity to service them - to match the new setup precisely, so your vehicle continues to feel perfect, no matter how much it’s changed.

I do raids and/or overlanding with my 4x4. Are Nimbus suspensions suitable for this?

Absolutely. Nimbus suspensions were designed with raids and overlanding in mind.

Whether you drive a Land Rover Defender, Jeep Wrangler, Toyota Land Cruiser, Ineos Grenadier or any other serious 4x4, Nimbus was built for your kind of terrain and your kind of adventures.

What sets our oleo-pneumatic technology apart is its ability to adapt to the varying loads that come with overlanding. Rooftop tents, onboard power systems, water tanks, recovery tools, spare parts, and full camp setups can significantly change the weight and balance of your vehicle. With Nimbus, all it takes is a simple pressure adjustment to restore the ride quality, stability, and comfort of your 4x4, even under full load.

And when you return from the journey and strip your vehicle back down for daily use? Just drop the pressure, and your now-lighter 4x4 will feel perfectly balanced again. No need to change parts, just adapt the pressure to the mission.

But it’s not just about weight. Nimbus dramatically improves comfort and control, even on the harshest tracks. By reducing fatigue on both the driver and the vehicle, you protect your back, your passengers, and your chassis, all while enjoying a ride quality few expect on such rugged terrain.

And in case you're wondering about toughness: the very same Nimbus suspension platform is used by vehicles competing in the Dakar Rally. Aside from personalized tuning, it’s the same system you receive when you order from us, proven in the most brutal conditions on the planet.

Built for the long haul, wherever you go, and however far you push it.

Will these suspensions work if I do a lot of off-roading on the weekends but drive on asphalt during the week?

Absolutely.

Nimbus suspensions are designed to perform across all types of terrain, from smooth asphalt to the most demanding off-road trails. In fact, we often say that a well-maintained track and a paved road are more alike than different, and what can handle more can certainly handle less.

Unless your vehicle is a pure rock crawler or competition rig - where we’d build a very specific setup - our standard oleo-pneumatic system is perfectly suited for mixed-use.

Daily commutes, work trips, and highway drives during the week, followed by rugged, technical terrain on the weekends? That’s exactly what Nimbus was made for. Whether it’s city roads, corrugations, gravel, or rocky tracks, Nimbus delivers stable, responsive damping and rebound that adapts to the terrain and protects both your vehicle and your spine.

That said, it’s important to be transparent:

Suspensions only show their true value when they’re challenged.

At low speeds or on a smooth highway, you may not always feel the dramatic difference because there’s not much for the suspension to react to. Nimbus isn’t built to turn a highway drive into a magic trick. It’s built to transform your experience when the terrain requires it, where traditional shocks reach their limits.

Also, keep in mind that some vehicles have built-in design or geometry limitations that no suspension can fully override. We engineer each setup to work as best as possible within those constraints, and we tell you all the benefits you will get from your Nimbus, but we also want to keep your expectations realistic, and not selling you too much of a dream.

So yes! Nimbus will give you the best of both worlds.

But its true value shines when the road disappears, and the terrain starts testing your gear. That’s where Nimbus steps up, and never lets go.

Nimbus Suspensions is a young company. How can I trust your products?

It's true. Nimbus is a young company.

But behind the name is a team with decades of combined experience in suspension engineering, oleo-pneumatic systems, off-road racing, and building solid, sustainable businesses. We’re not new to this, we’ve simply chosen to bring something new to the suspension world.

Our approach is intentionally measured: we’re not here to grow fast. We’re here to build the best suspensions we can.

That means prioritizing performance, reliability, and continuous improvement over mass production or hype.

And our suspensions are not theoretical. They’re already out in the world, on vehicles used daily for work, play, and competition in some of the harshest environments on the planet. From the dunes of the Sahara to the tracks of the Australian Outback, from the Icelandic highlands to South America’s Ruta 40 and even the streets of Miami (!), our clients push Nimbus systems to the edge, and send us their feedback so we can push even further.

We’re proud of what we’ve achieved so far, but even more excited about what’s to come. No one can predict the future but with the right team, the right product, and the right mindset, you can feel confident we’re here for the long haul.

And if you’re ever in doubt, just ask the people who already drive on Nimbus, they’ll tell you what words alone can’t.

How much travel do the suspensions have?

It depends on your vehicle’s make and model.

Each Nimbus kit is custom-developed for your 4x4, and travel varies based on the geometry and configuration of the suspension system.

As an example, for the Land Rover Defender:

• Our standard kit offers 225 mm of travel in the front and 230 mm in the rear.

• The +5 cm version increases travel to 250 mm in the front and 255 mm in the rear.

If you’d like to know the travel for your specific vehicle, just send us a quick email. Our team will get back to you shortly with the exact figures for your setup.

Do you use polyurethane or rubber spacers?

We actually use both, strategically.

Our suspension systems are designed with a mix of polyurethane and rubber elements, depending on their position and function, to strike the right balance between flexibility, durability, and precision.

Let’s take the Land Rover Defender as an example to explain how we approach this:

• Front upper mount: We use a fixed rod with a stack of two 80 Shore polyurethane elastomers. Nimbus suspensions carry more load than conventional shocks, so this increased stiffness is necessary for performance. To protect the polyurethanes from tearing under movement, we add two 3 mm FKM rubber washers on the chassis side, which introduce just the right amount of flexibility.

• Front lower mount: This point uses a control-arm-style ball joint, offering excellent angular movement while maintaining the stiffness required for the oleo-pneumatic system to operate efficiently.

• Rear upper mount: Here, we’ve developed a hybrid system that combines the benefits of a silent block and a ball joint. It uses a Kevlar-reinforced bearing that doesn’t require lubrication, sandwiched between spacers and rubber pads to control unwanted movement and extend the ball joint’s lifespan. We even supply dedicated upper mounts to guarantee the tolerances between the spacers and the support rod meet our exact specs.

• Rear lower mount: This is identical to the front lower setup, with a ball joint optimized for angular recovery during large suspension movements.

Of course, this is just one example. Our approach varies by vehicle, depending on its chassis design, travel geometry, and mounting architecture. But across all platforms, our use of polyurethane and rubber isn’t arbitrary. Every material and mounting choice is made to ensure longevity, performance, and compatibility with the unique demands of each 4x4.

and if you've got even more questions: Let's Talk

At Nimbus, we understand that exploring new technology can raise many questions.

Our innovative suspensions are crafted with your comfort and performance in mind, and we're here to answer any questions you may have and support you every step of the way.

Contact us to learn how Nimbus can make such a difference for your vehicle.

- We’re here to help, not to hustle. Reach out anytime. No pressure, no scripts, just honest advice -

Skip the Email – Give Us a Call!

NIMBUS COLORADO

Denver

Rodrigo Vasquez

+1 (720) 340-1646

NIMBUS NORTH CAROLINA

Raleigh

Greg Dietz

+1 (336) 264-6686

NIMBUS FLORIDA

Palm Beach Gardens

Pierre-Olivier Carles

+1 (561) 231-0050

NIMBUS NORDIC

Falkenberg - Sweden

Jasper den Boer

+31 6 29582061

NIMBUS UK

Yorkshire

Chris Rhodes

+44 7887 631 062

NIMBUS GULF

Dubai - UAE

Muhammad Asim

+971 502295511

NIMBUS AUSTRALIA

Victoria - Australia

Rohan Cooray

+61 434 999 000

NIMBUS FRANCE

Labarthe-Inard

Killian Carles

+33 5 31 51 10 20

[email protected]

We’re located in the United States, France, the UK, Australia, the Nordics and the UAE. Click here to find your nearest location.

© 2026 Nimbus Suspensions Inc

General Terms of Sales - Privacy policy

All brand names, logos, and trademarks featured or referred to on this website are the property of their respective trademark holders. We are not affiliated with, endorsed by, or sponsored by these trademark holders. Use of these names, logos, or trademarks is solely for identification purposes to inform customers about the aftermarket products we offer for their vehicles.